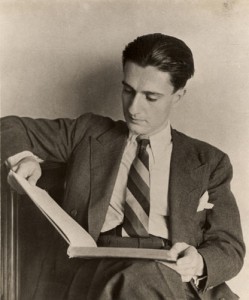

One of the misperceptions about Dinu Lipatti is that he had a small repertoire. Because he only recorded two piano concertos for EMI – Schumann and Grieg’s sole concertos, both in A Minor – and because (inaccurate) stories circulated that he required three and four years respectively to prepare the Tchaikovsky and Emperor Concertos (absolutely not true – details in the Prince of Pianists article), there is the idea that he played very few concerted works. But before his death at the age of 33, Lipatti had in fact publicly performed twenty-three works for piano and orchestra (including works not classified as concertos, like Stravinsky’s Capriccio) and had a larger private repertoire that included works like Ravel’s Left-Hand Concerto – his copy of the score at the Geneva Conservatory is laced with fingerings from his student days in Paris in the 1930s. (He was in fact scheduled to record the Bartok Third with Karajan and the Philharmonia in November 1949, but the session was canceled due to Lipatti’s inability to travel to London).

One of the misperceptions about Dinu Lipatti is that he had a small repertoire. Because he only recorded two piano concertos for EMI – Schumann and Grieg’s sole concertos, both in A Minor – and because (inaccurate) stories circulated that he required three and four years respectively to prepare the Tchaikovsky and Emperor Concertos (absolutely not true – details in the Prince of Pianists article), there is the idea that he played very few concerted works. But before his death at the age of 33, Lipatti had in fact publicly performed twenty-three works for piano and orchestra (including works not classified as concertos, like Stravinsky’s Capriccio) and had a larger private repertoire that included works like Ravel’s Left-Hand Concerto – his copy of the score at the Geneva Conservatory is laced with fingerings from his student days in Paris in the 1930s. (He was in fact scheduled to record the Bartok Third with Karajan and the Philharmonia in November 1949, but the session was canceled due to Lipatti’s inability to travel to London).

Hints of hidden treasure

I first heard of his having played the Bartok Third Concerto when reading in the late 1980s a commemorative text written by his student Jacques Chapuis in one of the memorial books published by Labor et Fides (available here), in which he spoke about Lipatti’s premiering the work with Ansermet at a concert for which the orchestral scores had arrived the day of the concert (this was in fact the Swiss premiere of the work, not the world or European premieres, and took place in November 1947). Of course the thought of Lipatti performing a modern work from the standard repertoire was enthralling to say the least. I wondered if a broadcast might exist of this performance. And so the search began.

I first heard of his having played the Bartok Third Concerto when reading in the late 1980s a commemorative text written by his student Jacques Chapuis in one of the memorial books published by Labor et Fides (available here), in which he spoke about Lipatti’s premiering the work with Ansermet at a concert for which the orchestral scores had arrived the day of the concert (this was in fact the Swiss premiere of the work, not the world or European premieres, and took place in November 1947). Of course the thought of Lipatti performing a modern work from the standard repertoire was enthralling to say the least. I wondered if a broadcast might exist of this performance. And so the search began.

I was all the more motivated when reading through Judith Oringer’s book ‘Passion For Piano’, where in the section of recommended performers for different composers, she had in the Bartok section ‘Any recordings by the Rumanian pianist Dinu Lipatti or the Hungarian Gyorgy Sandor.’ I was stunned, as few people knew that Lipatti had played the Bartok and certainly none of the well-connected collectors that I knew had heard a recording of Lipatti playing anything by the Hungarian composer – and this included Gregor Benko (president of the International Piano Archives) and a number of European record collectors. (Oringer, in response to an inquiry while this article was in preparation, stated that she cannot recall how she heard of Lipatti’s name in relation to any recordings of Bartok compositions.)

In late 1989, I obtained a copy of Lipatti’s biography, a somewhat poorly translated effort of the Romanian original by Grigore Bargauanu and Dragos Tanasescu, and the back section of the discography listed a recording of Lipatti performing the Bartok Third Concerto in May 1948 with the Südwestfunk Orchestra conducted by Paul Sacher. There was a note that stated ‘The recording was never issued because the conductor did not consider it satisfactory.’ I stared at the page in disbelief: even if the conductor was not satisfied, if the recording was known to exist, how is it that even well-connected collectors didn’t have a copy?

Detective work

In these days before the internet, it wasn’t as easy to track down people and information. The first order of business was to contact the Südwestfunk – so I called up the German consulate and obtained the address (that’s what one did in the days before Google). I wrote to the SWF with the information I had from the biography, and waited. Three months later, I received a sheet of paper in the mail that had my address on it, a return address at the Südwestfunk, and some stamps on it – and nothing else. It appeared to be the label of a package, but the package was gone! I went to the local post office but they agreed that it looked as though it was a label that had come off a package. We filled out a form to hunt for the lost package, but they were not optimistic.

As there was a name on the return address, I called the radio station the next day (having obtained the number from the consulate) and spoke with that woman – she didn’t speak English, my German was basic, but we soon figured out that we both spoke French. “Oh yes, we sent you the recording,” she informed me. Well, it hadn’t arrived. I was devastated. I didn’t get the impression that they could be counted on to send me another copy, but I told her I was planning to go to Europe a few months later, and she invited me to stop by to see her at the station to obtain a copy.

And so I did. After a few days in Paris, I went directly to Baden-Baden, home of various spas and a radio station where Lipatti had performed Bartok’s Third Concerto 42 years earlier. It took a while to figure out how to get to the Südwestfunk by public transport, and by the time I got there, it was getting late in the day – and it was a Friday afternoon, so I was concerned about being too late at the end of the work week. It took a bit of running around from one building to the next to find my contact – despite their reputation for being organized, no one seemed to know where I should go, and after my bad luck with the lost package, I was worried at the prospect of not getting the tape. But finally, sweaty in the May heat, I met the lady whom I had spoken to on the phone some months before and she kindly handed me a cassette – letting me know, however, that for copyright reasons, a gap of a second or two had been inserted in each movement to prevent the recording from being illicitly issued.

Hands on

After leaving the SWF on the bus, I listened excitedly to the tape on a basic Walkman and was surprised by the performance – not in the way that I’d expected. It was a much slower performance than usual – the first movement lacked the frenetic momentum that one usually heard – and the orchestral playing wasn’t quite together. Additionally, there were some electronic bleeps midway through the first movement. The second movement, however, revealed Lipatti at his best – transparent chordal playing, beautiful voice-leading – and the third movement had beautifully layered voicing in the fugue, just like Lipatti’s legendary Bach. The unmastered sound quality was perhaps the best of all discovered Lipatti broadcast concerto performances, being the only one recorded on professional equipment.

I visited London a few weeks later and went to EMI’s headquarters, having been introduced by Bryan Crimp of the APR label. Charles Rodier, the legal man, was very kind and gracious and introduced me to Ken Jagger, who was in charge of historical releases. He asked if I could leave them a copy of the cassette so that the team could listen to it more attentively, and said they would be in touch with me.

A year later, I visited Europe again, and London was my first stop. I phoned up EMI and asked Mr. Jagger what they had decided about the Bartok. He appeared a bit flustered and asked me if I would mind calling back in a few days once he had the time to review the situation with his colleagues (in other words, he had completely forgotten). When I did call back, he stated that they found the playing substandard and that it would be a disservice to Lipatti to issue the recording.

First attempts

That same visit, I went to the EMI archives in Hayes with Bryan Crimp and came across correspondance that gave more background into the label’s history with this recording. It seems that in the 1960s, Lipatti’s producer Walter Legge was alerted to the existence of this Bartok recording while he was looking into another broadcast recording, that of the Chopin E Minor Concerto (described in more detail here). On July 4, 1963 Legge wrote to the German branch of EMI, the Electrola Gesellschaft mbH, to see if they could obtain the recording “from Frankfurt Radio they have under number 52 A 913 (Lautarchiv) M381/II + III (Baden-Baden) and Bela Bartok: Konzert nr 3 fur Klavier und Orchester Dinu Lipatti Südwestfunk-Orchester, dir: Paul Sacher (26’05”). I shall be most grateful if you can induce them to let you make a copy tape of this recording and if you will send it to us with a view to publishing it in disc form. I shall have no difficulty in obtaining permission from Lipatti’s widow or from the conductor.”

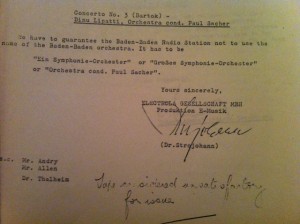

Famous last words. It took six months to get a tape – Lipatti’s widow Madeleine and conductor Paul Sacher had to send letters of consent for the radio stations to provide EMI with a copy, though Madeleine reported (in French) in a letter dated October 17, 1963 that “Paul Sacher believes that the recording will not be satisfactory and wishes to hear the tape.” When a tape did arrive, it was marred by the same electronic bleeps found on the cassette in 1990. Peter de Jongh wrote on June 3, 1964 that he had left a laquer (pressing) with Michael Allen of EMI and that in his opinion, “the performance by Lipatti is of the greatest interest. His incomparable musicianship, touch and vitality are all there.” On July 28, 1964, H.R. Stracke of Electrola wrote that “on principle, the orchestra agrees with the release. Price: DM 4.500, — provided that the regeneration (sic) is acceptable.” By October 13, the costs had been tallied as DM 4500 for the orchestra, DM 1560 for Boosey and Hawkes (DM 60 per minute), and DM 100 for the tape; by February 25, 1965, the radio station had asked for DM 2500 for the tape.  On September 27, 1965, Dr Strojohann of Electrola wrote that “We have to guarantee the Baden-Baden Radio Station not to use the name of the Baden-Baden orchestra. It has to be “Ein Symphonie-Orchester” or “GroBes Symphonie-Orchester” or “Orchestra cond. Paul Sacher”.” That became a moot point: an undated handwritten note at the bottom of the memo says ‘Tape considered unsatisfactory for issue.’

On September 27, 1965, Dr Strojohann of Electrola wrote that “We have to guarantee the Baden-Baden Radio Station not to use the name of the Baden-Baden orchestra. It has to be “Ein Symphonie-Orchester” or “GroBes Symphonie-Orchester” or “Orchestra cond. Paul Sacher”.” That became a moot point: an undated handwritten note at the bottom of the memo says ‘Tape considered unsatisfactory for issue.’

The matter was picked up again in 1970, but David Mottley of EMI wrote in a memo dated October 12, “Having listened to the tape of Lipatti playing Bartok’s 3rd Piano Concerto, I do not think it would be in the interests of anybody to attempt to issue this recording on disc. Not only is the reproduction quality very poor indeed but also the playing of the orchestra is of a low standard generally. Christopher Parker also confirms that there is nothing that can be done to improve the quality of sound on this tape.”

Back to the future

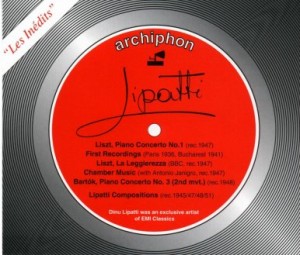

Fast-forward to 1991. EMI has once again, through Ken Jagger, issued the same opinion. Then, in 1992-1993, I introduced the Lipatti fan and collector Dr Marc Gertsch of Bern to Werner Unger of the German historical recordings label ‘archiphon’. Gertsch presented enough private Lipatti material to issue a two-disc set, and so the matter of the Bartok Concerto was raised again.  In an attempt to force Sacher’s hand, we had a colleague request the Südwestfunk to broadcast the recording, in the hopes that he would consent to an authorized release once the tape began to circulate privately in order to prevent an illicit release. He didn’t budge, though he did say that he would approve of issuing the second movement, as that was very beautiful. And so that movement was issued on a set entitled ‘Dinu Lipatti: Les Inedits’ . (This set has some items not released elsewhere and is currently available on iTunes here).

In an attempt to force Sacher’s hand, we had a colleague request the Südwestfunk to broadcast the recording, in the hopes that he would consent to an authorized release once the tape began to circulate privately in order to prevent an illicit release. He didn’t budge, though he did say that he would approve of issuing the second movement, as that was very beautiful. And so that movement was issued on a set entitled ‘Dinu Lipatti: Les Inedits’ . (This set has some items not released elsewhere and is currently available on iTunes here).

In May 1999, I was at the airport in Tokyo en route to Thailand when I read in Time magazine that Paul Sacher had died. I wondered how long it would take for the Bartok to come out, as it was more than 50 years after the performance and was therefore in the public domain. Not long later, the Italian label Urania issued the complete concerto – complete with the electronic bleeps that had marred the first movement. (The previous summer, Werner Unger and I had edited out the bleeps quite easily on a computer program.)

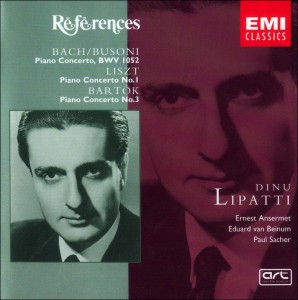

In 2000, I was focused on producing a memorial edition for the 50th anniversary of Lipatti’s death. Unger and I approached EMI and offered them a remastering we had made of Lipatti’s Chopin Concerto performance which was far superior to anything issued by the label (we had access to Gertsch’s original tape, which EMI had not touched since 1981). They declined, stating that they were satisfied with what they had, and they gave us permission to issue it ourselves. I suggested Unger ask EMI what they were doing for the Lipatti anniversary – and the response was something along the lines of, ‘Um… what do you suggest?’ They had neglected to prepare a commemorative release for this universally loved and best-selling artist. I proposed that they issue the Bach-Busoni D Minor, Liszt E-Flat, and Bartok Third concertos on a single CD – something I had suggested back in 1991 shortly after learning of the existence of the Liszt Concerto in Dr. Gertsch’s collection. Now they finally agreed. When I wrote to them to ask about contributing the liner notes, they wrote back that they had already assigned it to one of their writers but ‘Thank you for your interest in our project.’

[A side note: for a commorative issue, Unger and I had hoped to issue the Chopin Concerto – from 1950 – with three radio interviews from the same year, but Tahra issued two of the three interviews, so we opted instead to produce a release that spanned the whole of Lipatti’s recording career, from 1936 to 1950: ‘Cornerstones’. Like the previous archiphon set, this release has some otherwise unissued Lipatti recordings and is available on iTunes here.]

In early 2001, EMI’s release of three concert performances by Dinu Lipatti of piano concertos that he had not officially recorded and spanning three centuries of the repertoire was finally made available to the general public. (Available on iTunes here and on CD via Amazon here, as well as in this 7-disc set of his EMI recordings.) Critical acclaim of the performances was immediate – no one felt that the substandard orchestral support in the Bartok was an issue, and EMI used the edited version of the tape that Unger and I had prepared so that the bleeps were not an issue. (Unfortunately, the sound of the issued disc is worse than the masters we provided them, particularly in the Bach-Busoni and Liszt.)

In early 2001, EMI’s release of three concert performances by Dinu Lipatti of piano concertos that he had not officially recorded and spanning three centuries of the repertoire was finally made available to the general public. (Available on iTunes here and on CD via Amazon here, as well as in this 7-disc set of his EMI recordings.) Critical acclaim of the performances was immediate – no one felt that the substandard orchestral support in the Bartok was an issue, and EMI used the edited version of the tape that Unger and I had prepared so that the bleeps were not an issue. (Unfortunately, the sound of the issued disc is worse than the masters we provided them, particularly in the Bach-Busoni and Liszt.)

The performance

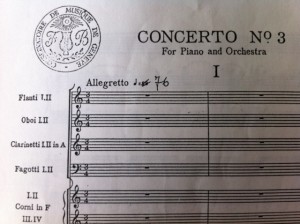

As to the performance itself: Lipatti takes the first movement at a slower rate than Bartok’s metronome markings, and as can be seen in this photograph from his own score of the work, he adjusted the marking from 88 to 76.  While Lipatti is seen as having considered the text as sacrosanct, the fact is that the energy of the composition took priority, and a number of musicologists have spoken to Bartok’s tempo indications often being too fast. His slower pace in this movement highlights the melancholic experience the composer was going through as he wrote this work. Lipatti phrases fluidly rather than frenetically, emphasizing the lyrical and harmonic rather than the overtly rhythmic.

While Lipatti is seen as having considered the text as sacrosanct, the fact is that the energy of the composition took priority, and a number of musicologists have spoken to Bartok’s tempo indications often being too fast. His slower pace in this movement highlights the melancholic experience the composer was going through as he wrote this work. Lipatti phrases fluidly rather than frenetically, emphasizing the lyrical and harmonic rather than the overtly rhythmic.

The second movement is one of the most profoundly moving examples of Lipatti’s art. His voicing in the chorale is sublime: every chord is weighted such that primary and inner tones ring in perfect balance, each successive collection of tone clusters resonating at its own particular vibration, fading seamlessly into its successor. Never have both the vertical and horizontal lines of this chorale been so flawlessly executed. The middle section of the movement is beautifully played (it is eerily like the middle section of the third movement (of four) of Lipatti’s own Concertino in Classical Style), and builds magically to the final cadenza of the movement, which Lipatti plays with tremendous force: again, he voices with incredible attention, observing the composer’s pedal markings meticulously so that certain chords create a sonic envelope in which others are found.

The third movement, while suffering from some sloppy orchestral ensemble, features magically transparent voicing from Lipatti (particularly in the fugue, from 19:16 to 20:17), incredible accenting, amazing pedaling, and fantastic tonal effects. While the pianist may have been held back somewhat by the rather unskilled accompaniment, he nevertheless gives a thoroughly profound performance.

It is incredible to consider how we now have such easy access to a recording that was once unknown and considered the stuff of legend. Technology now enables music lovers the world over to listen to a performance that may well have lain dormant in the archives. May this recording serve to give more insight into Lipatti’s art, and may other lost recordings be added to his discography.

Bartok Piano Concerto No.3

Dinu Lipatti, piano

SWF Symphony Orchestra

Paul Sacher, conductor

May 30, 1948