I am delighted to share some news that is thrilling for Dinu Lipatti fans:

The first known film footage of the great pianist has been located.

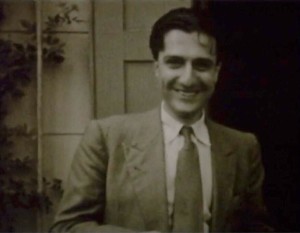

Although he is not at the piano and there are only about 10 seconds of him in this silent film, it is tremendously exciting to see him ‘in action’, so to speak. The film was made at a garden party in Lucerne in 1947 at which Hindemith, Furtwängler, Schwarzkopf, Aeschbacher, Sacher, and other celebrated musicians – as well as his own fiancée Madeleine – were in attendance.

The home movie was discovered and obtained by Orlando Murrin, who has in the last two years done some remarkable research into Lipatti’s life, following avenues not explored by other Lipatti researchers such as myself – and what fruit his efforts have borne!

I have seen the footage and it is utterly remarkable and very moving. Lipatti appears more at ease than he does in the famous posed photographs that have circulated for decades, with a wonderfully warm broad smile, at one moment combing his hand through his hair while in conversation in a most natural way. We get to see him as a ‘human’ and not the deified image that was perpetuated after his premature death.

I have seen the footage and it is utterly remarkable and very moving. Lipatti appears more at ease than he does in the famous posed photographs that have circulated for decades, with a wonderfully warm broad smile, at one moment combing his hand through his hair while in conversation in a most natural way. We get to see him as a ‘human’ and not the deified image that was perpetuated after his premature death.

Murrin will be screening the film at the pre-concert talk for a Lipatti centenary tribute concert at Cadogan Hall in London on November 28. At the concert, Romanian pianist Alexandra Dariescu will play the Grieg Concerto – one of the cornerstones of Lipatti’s performing career – as well as Lipatti’s own Concertino in Classical Style. Here a link with the details of the concert: http://www.cadoganhall.com/event/royal-philharmonic-orchestra-171128/

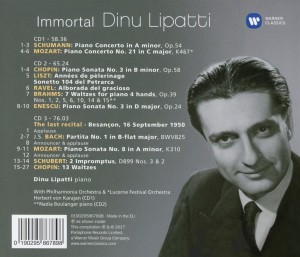

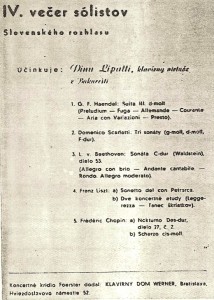

It is to be hoped that the existence of this private film will lead to the discovery of more footage of the great pianist and that a documentary featuring this and other Lipatti discoveries will be produced. Previously unpublished letters are being released in Romania, and these too reveal a very different side to Lipatti (very funny and witty, with astute observations about music, musicians, and business). And 15 minutes of unreleased recordings of Scarlatti and Brahms show a much more daring, bold, and impetuous side to his artistry.

Details about all of these publications will follow.