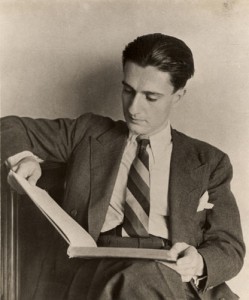

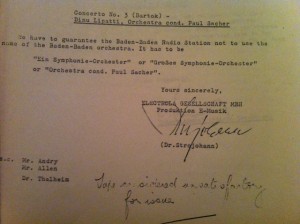

Dinu Lipatti signed his contract with the Columbia label of EMI in January 1946, and at his first session at a studio in Zurich that July he recorded three works: Chopin’s Waltz in A-Flat Op.34 No.1, Liszt’s Sonetto del Petrarca No.104, and Liszt’s La Leggierezza. (The exact date of the session is unknown: Lipatti wrote prior to the session that he was scheduled to make a series of recordings from July 4 to 6, but only recorded these 3 titles and so likely it took place on one of these days.) Columbia was experimenting with a new recording material, and the masters which were pressed warped while in transit to London. Engineers attempted to press the records, but they were unsalvageable. While Lipatti would once again record the Chopin Waltz – as a filler for the Grieg Concerto – and the Sonetto del Petrarca, both on September 24, 1947 at London’s Abbey Road Studio No.3, he did not make another attempt at La Leggierezza. While pitch-correcting technology could be used today to repair the damage to the 1946 recordings, no test pressings have been found and the record pressing master stampers have been destroyed. The recording sheet reproduced here lists October 15, 1946 as the date for a recording made at Abbey Road, but this is incorrect (as the handwritten note ‘Recorded in Switzerland’ indicates) and is undoubtedly the date of the attempted pressing of the disc.

Dinu Lipatti signed his contract with the Columbia label of EMI in January 1946, and at his first session at a studio in Zurich that July he recorded three works: Chopin’s Waltz in A-Flat Op.34 No.1, Liszt’s Sonetto del Petrarca No.104, and Liszt’s La Leggierezza. (The exact date of the session is unknown: Lipatti wrote prior to the session that he was scheduled to make a series of recordings from July 4 to 6, but only recorded these 3 titles and so likely it took place on one of these days.) Columbia was experimenting with a new recording material, and the masters which were pressed warped while in transit to London. Engineers attempted to press the records, but they were unsalvageable. While Lipatti would once again record the Chopin Waltz – as a filler for the Grieg Concerto – and the Sonetto del Petrarca, both on September 24, 1947 at London’s Abbey Road Studio No.3, he did not make another attempt at La Leggierezza. While pitch-correcting technology could be used today to repair the damage to the 1946 recordings, no test pressings have been found and the record pressing master stampers have been destroyed. The recording sheet reproduced here lists October 15, 1946 as the date for a recording made at Abbey Road, but this is incorrect (as the handwritten note ‘Recorded in Switzerland’ indicates) and is undoubtedly the date of the attempted pressing of the disc.

Fast-forward to 1990. I was in London hoping to find more Lipatti recordings and paid a visit to the National Sound Archive, which was then located on Exhibition Road in Kensington. I searched through their card catalogue, which is what one did in the days before the internet, but there was nothing under Lipatti. I then had a hunch to search through the composers he’d performed just in case something was not properly cross-referenced – and sure enough… under Liszt, there was listed a recording on tape 101W of Dinu Lipatti playing La Leggierezza. It said that it had been recorded from a BBC broadcast by one D Steynor and obtained by the British Institute of Recorded Sound on October 21, 1958. I requested to listen to the tape, and was flabbergasted by the playing. The opening few measures were missing and there was a big pitch fluctuation near the beginning of the recording, but other than that and the somewhat restricted tonal range, one could clearly hear Lipatti’s unique pianism.

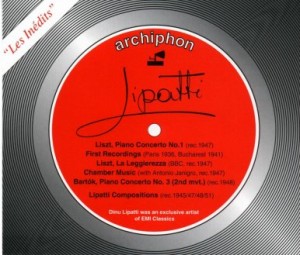

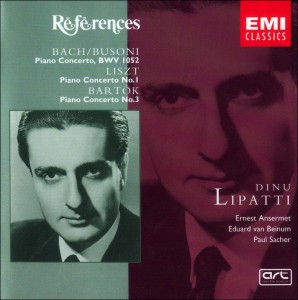

A couple of years later when I returned to London, I met with the staff to discuss the recording. As Werner Unger of archiphon records and I were formulating plans to obtain and release some lost Lipatti recordings, we wanted to discuss the possibility of obtaining a copy of the tape. The staff of the NSA were very accommodating, and we listened to the recording together. Their engineers, with their incredibly trained ears, could recognize the acoustic as being a BBC studio, whereas I had thought this might still be a broadcast of a test pressing of the unpublished EMI recording. Later research revealed that Lipatti did in fact broadcast the work from the BBC studios on September 25, 1947. The staff at the National Sound Archive said that if we could obtain permission from the BBC, they would be able to copy us the tape (we needed to show that the broadcast took place before July 1957 – something that was easy since Lipatti died in 1950). Unger handled that side of things, and the BBC were – rather surprisingly, given the stories that I’d heard – gracious not only in allowing us to have a copy of the NSA’s tape but also in consenting to its commercial release. In late 1994 we issued it on the archiphon CD set ‘Les Inédits’, its only authorized CD release to date.

The playing in this performance is phenomenal, and there are a few nuances that are particularly worth noting. Throughout the work, the bassline is remarkably clear, something that all Romantic pianists did in their playing – scores did not indicate that a line in the bass with step-wise progression should be highlighted because everyone at the time knew that it should be done. At 1:13 to 1:17, Lipatti voices the chords in the right hand such that the atonal quality of the harmonies stand out, highlighting the avant-garde nature of Liszt’s writing. In the section beginning at 2:52, as Lipatti moves from ascending to descending runs, he accelerates as he ‘goes around the corner’, so to speak, which produces a wonderfully ‘light’ effect. And then at 3:41-3:44, where every pianist that I’ve heard slows down and plays a decrescendo, Lipatti does the exact opposite, speeding up and crashing into a fortissimo in a grand, heroic gesture.

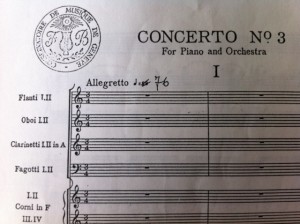

While we can lament the lack of more Liszt recordings by Lipatti – if only he’d played the Sonata! – we do have a greater idea of his approach to this great composer through the recordings that have come to light, among them an early test recording of Gnomenreigen, a 1947 concert recording of the First Concerto, and this current recording. (There will be other posts to follow on Gnomenreigen and the First Concerto.) We can keep our hopes alive that a broadcast recording of Liszt’s Second Concerto, which he played in concert many times, will one day surface. In the meantime, enjoy the one BBC broadcast of Dinu Lipatti that has come to light: the September 25, 1947 broadcast of Liszt’s La Leggierezza [note that the date on the YouTube video is inaccurate].