The only biography of Dinu Lipatti published in English is still available. 'Lipatti', written by Grigore Bargauanu and Dragos Tanasescu, was first published in 1971 and has been edited several times to reflect new information about Lipatti that has come to light. It is currently available by Kahn & Averill publishers at this link. This book is heartily recommended for any Lipatti fans who wish to learn more about the pianist. It includes biographical details, with extensive quotes from letters, as well as separate sections about Lipatti as an interpreter and as a composer.

The only biography of Dinu Lipatti published in English is still available. 'Lipatti', written by Grigore Bargauanu and Dragos Tanasescu, was first published in 1971 and has been edited several times to reflect new information about Lipatti that has come to light. It is currently available by Kahn & Averill publishers at this link. This book is heartily recommended for any Lipatti fans who wish to learn more about the pianist. It includes biographical details, with extensive quotes from letters, as well as separate sections about Lipatti as an interpreter and as a composer.

Dinu Lipatti biography still in print

September 3, 2016 by

The only biography of Dinu Lipatti published in English is still available. 'Lipatti', written by Grigore Bargauanu and Dragos Tanasescu, was first published in 1971 and has been edited several times to reflect new information about Lipatti that has come to light. It is currently available by Kahn & Averill publishers at this link. This book is heartily recommended for any Lipatti fans who wish to learn more about the pianist. It includes biographical details, with extensive quotes from letters, as well as separate sections about Lipatti as an interpreter and as a composer.

The only biography of Dinu Lipatti published in English is still available. 'Lipatti', written by Grigore Bargauanu and Dragos Tanasescu, was first published in 1971 and has been edited several times to reflect new information about Lipatti that has come to light. It is currently available by Kahn & Averill publishers at this link. This book is heartily recommended for any Lipatti fans who wish to learn more about the pianist. It includes biographical details, with extensive quotes from letters, as well as separate sections about Lipatti as an interpreter and as a composer.

Liszt’s First Piano Concerto

June 6, 2013 by

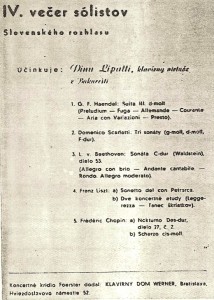

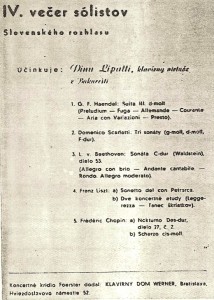

Dinu Lipatti recorded only two piano concertos for EMI - the Grieg and Schumann Concertos, both in A Minor, and both mainstays of the repertoire. While the Grieg has its more virtuosic side, somehow Lipatti's lyricism and musicality have overshadowed his more stunning technical feats in this performance, leaving pianophiles with the impression that he wasn't the kind of pianist who could play real showpieces. In the digital age and through this blog and other publications it is becoming more known that Lipatti played 23 works for piano and orchestra of all kinds. One of the works that figured in his repertoire for the longest was Liszt's First Piano Concerto.

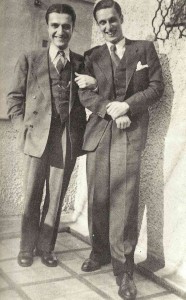

Lipatti first played the work in 1933 in Bucharest, and famously performed it with Mengelberg a decade later. Apparently when Lipatti came on the stage for the first rehearsal, Mengelberg said "Das ist kein Liszt-spieler" ("That is no Liszt pianist") - but once the pianist started playing, the conductor soon revised his assessment. Despite his rather slight appearance, Lipatti had strength in spades, and even though his approach to playing was always musical, he was capable of fireworks.

The last time that Lipatti played the work was on June 6, 1947 in Geneva, with the Radio Suisse Romande orchestra conducted by Ernest Ansermet, at a charity concert for the Red Cross. It came to my attention in 1991 that this performance had been recorded and preserved on a set of acetates owned by Lipatti's widow. I could not fathom at the time - nor can I still - why she possessed this recording yet seems to have made no effort to have it issued: there is not a shred of correspondence relating to its existence in EMI's archive. Nevertheless, along with other private recordings, these discs found their way into the hands of Dr. Marc Gertsch, a Lipatti fan in Bern who had come to the rescue of Mrs. Lipatti when the Chopin Concerto scandal had erupted (Gertsch had a recording of an authentic performance and let EMI use it once it was discovered that the recording they had released was not of Lipatti). After Mrs Lipatti died in the early 1980s, Gertsch was allowed to go into her collection and take the records he wanted; he did not take them all at once, and when he returned, those he had left were gone... meaning that there are potentially more private recordings that exist in private hands.

The copies of the Liszt Concerto were well worn, having been played multiple times, and the first record was cracked. While there was a backup reel tape, the sound was not very good on it. My colleague Werner Unger of the archiphon record label met with Gertsch in 1992 and took the recordings to remaster them. He spent hours and hours declicking and splicing the first record into an accurate representation of the performance (having heard the unedited transfer of the disc, with the needle jumping and skipping, I am in utter amazement at how he managed). We released the performance for the first time on archiphon's 'Les Inedits' box set release, which featured other unissued Lipatti performances from Gertsch's collection. Alas, some of the final mastering by one of Unger's colleagues removed some of the full-bodied sound that had previously been present in the Liszt.

In 2000, Unger and I were in discussion about Lipatti matters and I suggested he ask EMI what they had prepared for the 50th anniversary of Lipatti's death so that we could release our own commemorative CD. When it became evident that they had completely missed the occasion and not planned to issue anything, they asked us what we had that they could use, and I proposed the Bach-Busoni, Liszt, and Bartok Third Concertos as a single disc. The CD was eventually issued in early 2001, so this glowing performance of Liszt's First Concerto is now part of Lipatti's official discography. (I offered to write the booklet notes for the CD but was told that one of their regular writers would do so, and they thanked me for my interest in their project.) Alas, EMI also continued to fiddle with the engineering after we'd approved of one fine transfer, further compressing and deadening the sound.

Regardless of sonic restrictions, the performance reveals some staggering playing on Lipatti's part, displaying his unique synthesis of thorough technical command and profound, poised musicality. He has a massive dynamic range (recent digital transfers of the Grieg Concerto give a better idea) and plays with peaked phrasing, crisply defined articulation, dramatic emphasis, and elegant rubato. His tempi would be considered spacious by modern standards: in 1930s Paris, he heard Liszt's pupil Emil von Sauer play both concertos and was impressed with his slower tempi and refined approach. In the third movement, Lipatti achieves the remarkable 'bounce' heard on his legendary disc of Ravel's Alborada del Gracioso, and the cadenza in that movement (starting around 13:07 on the YouTube clip below) is the most convincing I've heard: he slows down and plays with a rumbling bass, arching the phrasing of the melody in a truly sinister fashion that seems so natural and obvious that I can't understand why other pianists haven't considered this approach.

Lipatti played the Chopin Andante Spianato and Polonaise at the same concert but a recording of that performance has not been found. It is to be hoped that it is among those that went missing from Mrs Lipatti's collection and will one day be recovered. But fortunately we now have this amazing performance of Liszt's First Piano Concerto readily available on CD, at iTunes, and on YouTube for all to enjoy.

Lipatti first played the work in 1933 in Bucharest, and famously performed it with Mengelberg a decade later. Apparently when Lipatti came on the stage for the first rehearsal, Mengelberg said "Das ist kein Liszt-spieler" ("That is no Liszt pianist") - but once the pianist started playing, the conductor soon revised his assessment. Despite his rather slight appearance, Lipatti had strength in spades, and even though his approach to playing was always musical, he was capable of fireworks.

The last time that Lipatti played the work was on June 6, 1947 in Geneva, with the Radio Suisse Romande orchestra conducted by Ernest Ansermet, at a charity concert for the Red Cross. It came to my attention in 1991 that this performance had been recorded and preserved on a set of acetates owned by Lipatti's widow. I could not fathom at the time - nor can I still - why she possessed this recording yet seems to have made no effort to have it issued: there is not a shred of correspondence relating to its existence in EMI's archive. Nevertheless, along with other private recordings, these discs found their way into the hands of Dr. Marc Gertsch, a Lipatti fan in Bern who had come to the rescue of Mrs. Lipatti when the Chopin Concerto scandal had erupted (Gertsch had a recording of an authentic performance and let EMI use it once it was discovered that the recording they had released was not of Lipatti). After Mrs Lipatti died in the early 1980s, Gertsch was allowed to go into her collection and take the records he wanted; he did not take them all at once, and when he returned, those he had left were gone... meaning that there are potentially more private recordings that exist in private hands.

The copies of the Liszt Concerto were well worn, having been played multiple times, and the first record was cracked. While there was a backup reel tape, the sound was not very good on it. My colleague Werner Unger of the archiphon record label met with Gertsch in 1992 and took the recordings to remaster them. He spent hours and hours declicking and splicing the first record into an accurate representation of the performance (having heard the unedited transfer of the disc, with the needle jumping and skipping, I am in utter amazement at how he managed). We released the performance for the first time on archiphon's 'Les Inedits' box set release, which featured other unissued Lipatti performances from Gertsch's collection. Alas, some of the final mastering by one of Unger's colleagues removed some of the full-bodied sound that had previously been present in the Liszt.

In 2000, Unger and I were in discussion about Lipatti matters and I suggested he ask EMI what they had prepared for the 50th anniversary of Lipatti's death so that we could release our own commemorative CD. When it became evident that they had completely missed the occasion and not planned to issue anything, they asked us what we had that they could use, and I proposed the Bach-Busoni, Liszt, and Bartok Third Concertos as a single disc. The CD was eventually issued in early 2001, so this glowing performance of Liszt's First Concerto is now part of Lipatti's official discography. (I offered to write the booklet notes for the CD but was told that one of their regular writers would do so, and they thanked me for my interest in their project.) Alas, EMI also continued to fiddle with the engineering after we'd approved of one fine transfer, further compressing and deadening the sound.

Regardless of sonic restrictions, the performance reveals some staggering playing on Lipatti's part, displaying his unique synthesis of thorough technical command and profound, poised musicality. He has a massive dynamic range (recent digital transfers of the Grieg Concerto give a better idea) and plays with peaked phrasing, crisply defined articulation, dramatic emphasis, and elegant rubato. His tempi would be considered spacious by modern standards: in 1930s Paris, he heard Liszt's pupil Emil von Sauer play both concertos and was impressed with his slower tempi and refined approach. In the third movement, Lipatti achieves the remarkable 'bounce' heard on his legendary disc of Ravel's Alborada del Gracioso, and the cadenza in that movement (starting around 13:07 on the YouTube clip below) is the most convincing I've heard: he slows down and plays with a rumbling bass, arching the phrasing of the melody in a truly sinister fashion that seems so natural and obvious that I can't understand why other pianists haven't considered this approach.

Lipatti played the Chopin Andante Spianato and Polonaise at the same concert but a recording of that performance has not been found. It is to be hoped that it is among those that went missing from Mrs Lipatti's collection and will one day be recovered. But fortunately we now have this amazing performance of Liszt's First Piano Concerto readily available on CD, at iTunes, and on YouTube for all to enjoy.

Lipatti first played the work in 1933 in Bucharest, and famously performed it with Mengelberg a decade later. Apparently when Lipatti came on the stage for the first rehearsal, Mengelberg said "Das ist kein Liszt-spieler" ("That is no Liszt pianist") - but once the pianist started playing, the conductor soon revised his assessment. Despite his rather slight appearance, Lipatti had strength in spades, and even though his approach to playing was always musical, he was capable of fireworks.

The last time that Lipatti played the work was on June 6, 1947 in Geneva, with the Radio Suisse Romande orchestra conducted by Ernest Ansermet, at a charity concert for the Red Cross. It came to my attention in 1991 that this performance had been recorded and preserved on a set of acetates owned by Lipatti's widow. I could not fathom at the time - nor can I still - why she possessed this recording yet seems to have made no effort to have it issued: there is not a shred of correspondence relating to its existence in EMI's archive. Nevertheless, along with other private recordings, these discs found their way into the hands of Dr. Marc Gertsch, a Lipatti fan in Bern who had come to the rescue of Mrs. Lipatti when the Chopin Concerto scandal had erupted (Gertsch had a recording of an authentic performance and let EMI use it once it was discovered that the recording they had released was not of Lipatti). After Mrs Lipatti died in the early 1980s, Gertsch was allowed to go into her collection and take the records he wanted; he did not take them all at once, and when he returned, those he had left were gone... meaning that there are potentially more private recordings that exist in private hands.

The copies of the Liszt Concerto were well worn, having been played multiple times, and the first record was cracked. While there was a backup reel tape, the sound was not very good on it. My colleague Werner Unger of the archiphon record label met with Gertsch in 1992 and took the recordings to remaster them. He spent hours and hours declicking and splicing the first record into an accurate representation of the performance (having heard the unedited transfer of the disc, with the needle jumping and skipping, I am in utter amazement at how he managed). We released the performance for the first time on archiphon's 'Les Inedits' box set release, which featured other unissued Lipatti performances from Gertsch's collection. Alas, some of the final mastering by one of Unger's colleagues removed some of the full-bodied sound that had previously been present in the Liszt.

In 2000, Unger and I were in discussion about Lipatti matters and I suggested he ask EMI what they had prepared for the 50th anniversary of Lipatti's death so that we could release our own commemorative CD. When it became evident that they had completely missed the occasion and not planned to issue anything, they asked us what we had that they could use, and I proposed the Bach-Busoni, Liszt, and Bartok Third Concertos as a single disc. The CD was eventually issued in early 2001, so this glowing performance of Liszt's First Concerto is now part of Lipatti's official discography. (I offered to write the booklet notes for the CD but was told that one of their regular writers would do so, and they thanked me for my interest in their project.) Alas, EMI also continued to fiddle with the engineering after we'd approved of one fine transfer, further compressing and deadening the sound.

Regardless of sonic restrictions, the performance reveals some staggering playing on Lipatti's part, displaying his unique synthesis of thorough technical command and profound, poised musicality. He has a massive dynamic range (recent digital transfers of the Grieg Concerto give a better idea) and plays with peaked phrasing, crisply defined articulation, dramatic emphasis, and elegant rubato. His tempi would be considered spacious by modern standards: in 1930s Paris, he heard Liszt's pupil Emil von Sauer play both concertos and was impressed with his slower tempi and refined approach. In the third movement, Lipatti achieves the remarkable 'bounce' heard on his legendary disc of Ravel's Alborada del Gracioso, and the cadenza in that movement (starting around 13:07 on the YouTube clip below) is the most convincing I've heard: he slows down and plays with a rumbling bass, arching the phrasing of the melody in a truly sinister fashion that seems so natural and obvious that I can't understand why other pianists haven't considered this approach.

Lipatti played the Chopin Andante Spianato and Polonaise at the same concert but a recording of that performance has not been found. It is to be hoped that it is among those that went missing from Mrs Lipatti's collection and will one day be recovered. But fortunately we now have this amazing performance of Liszt's First Piano Concerto readily available on CD, at iTunes, and on YouTube for all to enjoy.

Lipatti first played the work in 1933 in Bucharest, and famously performed it with Mengelberg a decade later. Apparently when Lipatti came on the stage for the first rehearsal, Mengelberg said "Das ist kein Liszt-spieler" ("That is no Liszt pianist") - but once the pianist started playing, the conductor soon revised his assessment. Despite his rather slight appearance, Lipatti had strength in spades, and even though his approach to playing was always musical, he was capable of fireworks.

The last time that Lipatti played the work was on June 6, 1947 in Geneva, with the Radio Suisse Romande orchestra conducted by Ernest Ansermet, at a charity concert for the Red Cross. It came to my attention in 1991 that this performance had been recorded and preserved on a set of acetates owned by Lipatti's widow. I could not fathom at the time - nor can I still - why she possessed this recording yet seems to have made no effort to have it issued: there is not a shred of correspondence relating to its existence in EMI's archive. Nevertheless, along with other private recordings, these discs found their way into the hands of Dr. Marc Gertsch, a Lipatti fan in Bern who had come to the rescue of Mrs. Lipatti when the Chopin Concerto scandal had erupted (Gertsch had a recording of an authentic performance and let EMI use it once it was discovered that the recording they had released was not of Lipatti). After Mrs Lipatti died in the early 1980s, Gertsch was allowed to go into her collection and take the records he wanted; he did not take them all at once, and when he returned, those he had left were gone... meaning that there are potentially more private recordings that exist in private hands.

The copies of the Liszt Concerto were well worn, having been played multiple times, and the first record was cracked. While there was a backup reel tape, the sound was not very good on it. My colleague Werner Unger of the archiphon record label met with Gertsch in 1992 and took the recordings to remaster them. He spent hours and hours declicking and splicing the first record into an accurate representation of the performance (having heard the unedited transfer of the disc, with the needle jumping and skipping, I am in utter amazement at how he managed). We released the performance for the first time on archiphon's 'Les Inedits' box set release, which featured other unissued Lipatti performances from Gertsch's collection. Alas, some of the final mastering by one of Unger's colleagues removed some of the full-bodied sound that had previously been present in the Liszt.

In 2000, Unger and I were in discussion about Lipatti matters and I suggested he ask EMI what they had prepared for the 50th anniversary of Lipatti's death so that we could release our own commemorative CD. When it became evident that they had completely missed the occasion and not planned to issue anything, they asked us what we had that they could use, and I proposed the Bach-Busoni, Liszt, and Bartok Third Concertos as a single disc. The CD was eventually issued in early 2001, so this glowing performance of Liszt's First Concerto is now part of Lipatti's official discography. (I offered to write the booklet notes for the CD but was told that one of their regular writers would do so, and they thanked me for my interest in their project.) Alas, EMI also continued to fiddle with the engineering after we'd approved of one fine transfer, further compressing and deadening the sound.

Regardless of sonic restrictions, the performance reveals some staggering playing on Lipatti's part, displaying his unique synthesis of thorough technical command and profound, poised musicality. He has a massive dynamic range (recent digital transfers of the Grieg Concerto give a better idea) and plays with peaked phrasing, crisply defined articulation, dramatic emphasis, and elegant rubato. His tempi would be considered spacious by modern standards: in 1930s Paris, he heard Liszt's pupil Emil von Sauer play both concertos and was impressed with his slower tempi and refined approach. In the third movement, Lipatti achieves the remarkable 'bounce' heard on his legendary disc of Ravel's Alborada del Gracioso, and the cadenza in that movement (starting around 13:07 on the YouTube clip below) is the most convincing I've heard: he slows down and plays with a rumbling bass, arching the phrasing of the melody in a truly sinister fashion that seems so natural and obvious that I can't understand why other pianists haven't considered this approach.

Lipatti played the Chopin Andante Spianato and Polonaise at the same concert but a recording of that performance has not been found. It is to be hoped that it is among those that went missing from Mrs Lipatti's collection and will one day be recovered. But fortunately we now have this amazing performance of Liszt's First Piano Concerto readily available on CD, at iTunes, and on YouTube for all to enjoy.

Dinu Lipatti’s Final Essay – On Interpretation

March 28, 2013 by

Below is a draft from May 1950 of a presentation for an Interpretation Course to be held at the Conservatoire de Geneve. Lipatti had planned to give the course with Nadia Boulanger in the Spring of 1951. The text below was found in his papers after his death, and gives a good glimpse of his views towards interpretation.

It is unjustly believed that the music from one era or another must preserve the imprint, the characteristics, and even the vices prevalent at the time this music was created. In thinking this way we have a peaceful conscience and find ourselves incapable of any dangerous misrepresentation. And to reach this objective, for all the effort, for all the research done in the dust of the past, for all the useless scrupulousness towards the ‘sole object of our attention,’ we will always end up drowning it in an abundance of prejudices and false facts. For, let us never forget, true and great music transcends its time and, even more, never corresponded to the framework, forms, and rules in place at the time of its creation: Bach in his work for organ calls for the electric organ and its unlimited means, Mozart asks for the pianoforte and distances himself decisively from the harpsichord, Beethoven demands our modern piano, which Chopin - having it - first gives its colors, while Debussy goes further in presenting through his Preludes glimpses of Martenot’s Wave [i]. Therefore, wanting to restore to music its historical framework is like dressing an adult in an adolescent’s clothes. This might have a certain charm in the context of a historical reconstruction, yet is of no interest to those other than lovers of dead leaves or the collectors of old pipes.

These reflections came to me while recalling the astonishment that I caused some time ago when I played, at a prominent European music festival [ii], Mozart's D minor Concerto [K. 466] with the magnificent and stunning cadenza that Beethoven made for this work. True, we could sense that the same themes appear differently under Beethoven’s pen than under that of Mozart. But this is exactly wherein lies the appeal of this interesting confrontation between two such different personalities. I regret to say that other than a few enlightened spirits, nobody understood this marriage and everyone suspected that I had composed this vile and anachronistic cadenza!

How right Stravinsky is in affirming that 'Music is the present'!

Music has to live under our fingers, under our eyes, in our hearts and in our brains with all that we, the living, can offer it.

Far be it for me to promote anarchy and disdain for the fundamental laws which guide, along general lines, the coordination of a valid and pertinent interpretation. But I find it a grave mistake to lose oneself in researching useless details regarding the way in which Mozart would have played a certain trill or grupetto. As for myself, the diverse markings provided by excellent yet incomplete treatises compel me to decisively take the path to simplification and synthesis while immutably preserving some four or five fundamental principles of which I think you are aware (or at least, I suppose you are), and for the rest I rely on intuition, that second but no-less-precious intelligence, and to in-depth penetration of the work, which, sooner or later, ends up confessing the secret of its soul.

Never approach a score with eyes of the dead or the past, for they may bring you nothing more in return than Yorick's skull [iii]. Alfredo Casella rightly said that we must not be satisfied with merely respecting masterpieces, but we must love them.

This translation © Mark Ainley 2003

End notes

i. An invention by Maurice Martenot (1898-1980) based on his discovery that the recently invented radio tubes produced a certain ‘purity of vibrations’. He presented his unique instrument at the Paris Opera in 1928 (he had started his research in 1919) and a number of composers, particularly French, wrote works for it.

ii. Lipatti performed the Mozart D Minor Concerto at the Lucerne Music Festival on August 23, 1947, with Paul Hindemith conducting.

iii. This refers to the scene in ‘Hamlet’ where the protagonist finds the skull of his favourite clown from his childhood. Lipatti is most likely stressing that in searching for the exact style of interpretation in the past, we may end up with something that once contained life but no longer does.

Dinu Lipatti’s Repertoire – Solo Piano and Two-Piano Works

February 1, 2013 by

The following is a list of the works that Dinu Lipatti is known to have played in public. It is based on existing concert programs and letters that give evidence that Lipatti actually played these works in concert - his private repertoire was larger. Occasionally, the list - originally compiled by  Lipatti biographer Grigore Bargauanu and the collector Marc Gertsch, with a few additions made now - lacks some detail in terms of exact works: for example, Lipatti played at least six Chopin Preludes, but exactly which ones he performed are unknown. Many of the works - particularly the four Beethoven Sonatas and the Schubert B-Flat Sonata! - are from his early performing years in the 1930s; he played the Waldstein throughout his career, however, and not only in the last few years of his life as his recording engineer Walter Legge erroneously reported. Some of the works that he did play in his later years include Bach Prelude and Fugues, Schumann's Études Symphoniques, Ravel's Le tombeau de Couperin, and Chopin's Fourth Ballade.

It is an enticing list that makes the lack of more recordings by this unique artist all the more regrettable. Let us hope that some other concert broadcasts or private recordings will be found!

Works for Solo Piano and Two Pianos

Albéniz

Iberia, Book 1 - 1. Evocación

Iberia, Book 1 - 2. El Puerto

Iberia, Book 2 - 3. Triana

Navarra (transcribed by Lipatti)

Petite serenade

Andricu

Two Dances

Two Pieces Op.18

Bach

Chorale in G Major, BWV 147 "Jesu, Joy of Man's Desiring" (arr. Hess)

Chorale Prelude, "Ich ruf zu Dir, Herr Jesu Christ" BWV 639 (arr. Busoni)

Chorale Prelude, "Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland" BWV 659 (arr. Busoni)

English Suite No.3 in G Minor, BWV 808

Italian Concerto, BWV 971

Partita No.1 in B-Flat Major, BWV 825

Pastorale in F Major for organ, BWV 590 (transcribed Lipatti)

Phantasy in A Minor, BWV 904

Preludes and Fugues from the Well-Tempered Clavier (at least 4)

Prelude and Fugue in E Minor for organ, BWV 533

Siciliano from Flute Sonata, BWV 1031 (arr. Kempff)

Toccata in D Major, BWV 912

Toccata in C Major, BWV 564 (arr. Busoni)

Bartók

Allegro barbaro

Six Dances in Bulgarian Rhythm (Mikrokosmos Vol.6)

Sonata for Piano

Beethoven

Piano Sonata No.7 in D Major, Op.10 No.3

Piano Sonata No.17 in D Minor, Op.31 No.2

Piano Sonata No.21 in C Major, Op.53 "Waldstein"

Piano Sonata No.23 in F Minor, Op.57 "Appassionata"

Berkeley

Concert Polka for Two Pianos

Brahms

Capriccio in D minor, Op.116 No.7

Intermezzo in A Minor, Op.116 No.2

Intermezzo in E-Flat Major, Op.117 No.1

Intermezzo in B-Flat Minor, Op.117 No.2

Intermezzo in E-Flat Minor, Op.118 No.6

Intermezzo in C Major, Op.119 No.3

Variations on a Theme by Haydn for Two Pianos

Waltzes Op.39 for Two Pianos (Nos. 1, 2, 5, 6, 10, 14, 15 - and perhaps others)

Brero

Five Preludes

Bull

Variations for Keyboard

Byrd

Various Pieces for Keyboard

Casella

Sonatina

Chopin

Ballade No.4 in F Minor, Op.52

Barcarolle in F-Sharp Major, Op.60

Étude in A Minor, Op.10 No.2

Étude in G-Flat Major, Op.10 No.5

Étude in C Major, Op.10 No.7

Étude in F Major, Op.10 No.8

Étude in E Minor, Op.25 No.5

Étude in A Minor, Op.25 No.11

Mazurka in E Minor, Op.41 No.1

Mazurka in B Major, Op.41 No.2

Mazurka in C-Sharp Minor, Op.41 No.4

Mazurka in C-Sharp Minor, Op.50 No.3

Nocturne No.8 in D-Flat Major, Op.27 No.2

Polonaise in E-Flat Major, Op.22

Polonaise in F-Sharp Minor, Op.44

Polonaise-Fantaisie in A-Flat Major, Op.61

various Preludes Op.28 (at least 6)

Rondo in F Major, Op.5

Scherzo No.1 in B Minor, Op.20

Scherzo No.3 in C-Sharp Minor, Op.39

Scherzo No.4 in E Major, Op.54

Sonata No.3 in B Minor, Op.58

Waltzes Nos.1 through 14

Waltz Op. Posth (which one is unknown)

Debussy

Arabesque (No.1 or 2)

Estampes No.2, "La soiree dans Grenade"

Étude pour les arpèges composés (and possibly others)

L'isle joyeuse

Images Book 1 No.1: "Reflets dans l'eau"

Images Book 1 No.2: "Hommage a Rameau"

Preludes (various)

Dohnányi

Capriccio in F Minor, Op.28 No.6

Enescu

Piano Sonata No.1 in F-Sharp Minor, Op.24 No.1

Piano Sonata No.3 in D Major, Op.24 No.3

Suite No.2 in D Major, Op.10

Variations on an Original Theme for two pianos, Op.5

De Falla

Ritual Fire Dance

Fauré

Impromptu No.3 in A-Flat Major, Op.34

Nocturne No.1 in E-Flat Minor, Op.33

Françaix

Concertino for two pianos

Handel

Suite No.3 in D Minor, HWV 428

Jora

Jewish March Op.8

Klepper

Two Dances

Lazar

Two Bagatelles

Lipatti

Compositions of childhood

Romanian Dances for two pianos

Three Dances for two pianos

Nocturne

Phantasie for piano solo

Sonatina for left hand

Suite for two pianos

Liszt

Concert Etude, "La Leggierezza", S.144

Concert Etude, "Gnomenreigen", S.145

Harmonies du soir

Mephisto Waltz No.1

Sonetto del Petrarca No.104

Mihalovici

Deux pieces impromptues, Op.19

Mozart

Piano Sonata No. 8 in A Minor, K.310

Sonata for Two Pianos in D Major, K.448

Mozart-Busoni

Duettino concertante for two pianos

Negrea

Sonatine Op.8

Nottara

Two Dances

Poulenc

Six Nocturnes

Ravel

Miroirs No.4, "Alborada del gracioso"

Miroirs No.5, "La vallee des cloches"

Le tombeau de Couperin

La Valse for two pianos

Scarlatti

Piano Sonata in E Major, L.23

Piano Sonata in G Major, L.387

Piano Sonata in D Minor, L.413

Piano Sonata in B-Flat Major

Piano Sonata in F Major

Piano Sonata in G Minor

Schubert

Impromptu No.2 in E-Flat Major, D.899 No.2

Impromptu No.3 in G-Flat Major, D.899 No.3

Piano Sonata No.21 in B-Flat Major, D.960

Allegro in A Minor for two pianos, D.947

Schumann

Blumenstück, Op.19

Carnaval, Op.9

Études Symphoniques, Op.13

Novelette No.2 in D Major, Op.21

Stravinsky

Danse russe (from "Petrouchka")

Sonata for piano

Weber-Corder

Invitation to the Dance for two pianos

Lipatti biographer Grigore Bargauanu and the collector Marc Gertsch, with a few additions made now - lacks some detail in terms of exact works: for example, Lipatti played at least six Chopin Preludes, but exactly which ones he performed are unknown. Many of the works - particularly the four Beethoven Sonatas and the Schubert B-Flat Sonata! - are from his early performing years in the 1930s; he played the Waldstein throughout his career, however, and not only in the last few years of his life as his recording engineer Walter Legge erroneously reported. Some of the works that he did play in his later years include Bach Prelude and Fugues, Schumann's Études Symphoniques, Ravel's Le tombeau de Couperin, and Chopin's Fourth Ballade.

It is an enticing list that makes the lack of more recordings by this unique artist all the more regrettable. Let us hope that some other concert broadcasts or private recordings will be found!

Works for Solo Piano and Two Pianos

Albéniz

Iberia, Book 1 - 1. Evocación

Iberia, Book 1 - 2. El Puerto

Iberia, Book 2 - 3. Triana

Navarra (transcribed by Lipatti)

Petite serenade

Andricu

Two Dances

Two Pieces Op.18

Bach

Chorale in G Major, BWV 147 "Jesu, Joy of Man's Desiring" (arr. Hess)

Chorale Prelude, "Ich ruf zu Dir, Herr Jesu Christ" BWV 639 (arr. Busoni)

Chorale Prelude, "Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland" BWV 659 (arr. Busoni)

English Suite No.3 in G Minor, BWV 808

Italian Concerto, BWV 971

Partita No.1 in B-Flat Major, BWV 825

Pastorale in F Major for organ, BWV 590 (transcribed Lipatti)

Phantasy in A Minor, BWV 904

Preludes and Fugues from the Well-Tempered Clavier (at least 4)

Prelude and Fugue in E Minor for organ, BWV 533

Siciliano from Flute Sonata, BWV 1031 (arr. Kempff)

Toccata in D Major, BWV 912

Toccata in C Major, BWV 564 (arr. Busoni)

Bartók

Allegro barbaro

Six Dances in Bulgarian Rhythm (Mikrokosmos Vol.6)

Sonata for Piano

Beethoven

Piano Sonata No.7 in D Major, Op.10 No.3

Piano Sonata No.17 in D Minor, Op.31 No.2

Piano Sonata No.21 in C Major, Op.53 "Waldstein"

Piano Sonata No.23 in F Minor, Op.57 "Appassionata"

Berkeley

Concert Polka for Two Pianos

Brahms

Capriccio in D minor, Op.116 No.7

Intermezzo in A Minor, Op.116 No.2

Intermezzo in E-Flat Major, Op.117 No.1

Intermezzo in B-Flat Minor, Op.117 No.2

Intermezzo in E-Flat Minor, Op.118 No.6

Intermezzo in C Major, Op.119 No.3

Variations on a Theme by Haydn for Two Pianos

Waltzes Op.39 for Two Pianos (Nos. 1, 2, 5, 6, 10, 14, 15 - and perhaps others)

Brero

Five Preludes

Bull

Variations for Keyboard

Byrd

Various Pieces for Keyboard

Casella

Sonatina

Chopin

Ballade No.4 in F Minor, Op.52

Barcarolle in F-Sharp Major, Op.60

Étude in A Minor, Op.10 No.2

Étude in G-Flat Major, Op.10 No.5

Étude in C Major, Op.10 No.7

Étude in F Major, Op.10 No.8

Étude in E Minor, Op.25 No.5

Étude in A Minor, Op.25 No.11

Mazurka in E Minor, Op.41 No.1

Mazurka in B Major, Op.41 No.2

Mazurka in C-Sharp Minor, Op.41 No.4

Mazurka in C-Sharp Minor, Op.50 No.3

Nocturne No.8 in D-Flat Major, Op.27 No.2

Polonaise in E-Flat Major, Op.22

Polonaise in F-Sharp Minor, Op.44

Polonaise-Fantaisie in A-Flat Major, Op.61

various Preludes Op.28 (at least 6)

Rondo in F Major, Op.5

Scherzo No.1 in B Minor, Op.20

Scherzo No.3 in C-Sharp Minor, Op.39

Scherzo No.4 in E Major, Op.54

Sonata No.3 in B Minor, Op.58

Waltzes Nos.1 through 14

Waltz Op. Posth (which one is unknown)

Debussy

Arabesque (No.1 or 2)

Estampes No.2, "La soiree dans Grenade"

Étude pour les arpèges composés (and possibly others)

L'isle joyeuse

Images Book 1 No.1: "Reflets dans l'eau"

Images Book 1 No.2: "Hommage a Rameau"

Preludes (various)

Dohnányi

Capriccio in F Minor, Op.28 No.6

Enescu

Piano Sonata No.1 in F-Sharp Minor, Op.24 No.1

Piano Sonata No.3 in D Major, Op.24 No.3

Suite No.2 in D Major, Op.10

Variations on an Original Theme for two pianos, Op.5

De Falla

Ritual Fire Dance

Fauré

Impromptu No.3 in A-Flat Major, Op.34

Nocturne No.1 in E-Flat Minor, Op.33

Françaix

Concertino for two pianos

Handel

Suite No.3 in D Minor, HWV 428

Jora

Jewish March Op.8

Klepper

Two Dances

Lazar

Two Bagatelles

Lipatti

Compositions of childhood

Romanian Dances for two pianos

Three Dances for two pianos

Nocturne

Phantasie for piano solo

Sonatina for left hand

Suite for two pianos

Liszt

Concert Etude, "La Leggierezza", S.144

Concert Etude, "Gnomenreigen", S.145

Harmonies du soir

Mephisto Waltz No.1

Sonetto del Petrarca No.104

Mihalovici

Deux pieces impromptues, Op.19

Mozart

Piano Sonata No. 8 in A Minor, K.310

Sonata for Two Pianos in D Major, K.448

Mozart-Busoni

Duettino concertante for two pianos

Negrea

Sonatine Op.8

Nottara

Two Dances

Poulenc

Six Nocturnes

Ravel

Miroirs No.4, "Alborada del gracioso"

Miroirs No.5, "La vallee des cloches"

Le tombeau de Couperin

La Valse for two pianos

Scarlatti

Piano Sonata in E Major, L.23

Piano Sonata in G Major, L.387

Piano Sonata in D Minor, L.413

Piano Sonata in B-Flat Major

Piano Sonata in F Major

Piano Sonata in G Minor

Schubert

Impromptu No.2 in E-Flat Major, D.899 No.2

Impromptu No.3 in G-Flat Major, D.899 No.3

Piano Sonata No.21 in B-Flat Major, D.960

Allegro in A Minor for two pianos, D.947

Schumann

Blumenstück, Op.19

Carnaval, Op.9

Études Symphoniques, Op.13

Novelette No.2 in D Major, Op.21

Stravinsky

Danse russe (from "Petrouchka")

Sonata for piano

Weber-Corder

Invitation to the Dance for two pianos

Lipatti biographer Grigore Bargauanu and the collector Marc Gertsch, with a few additions made now - lacks some detail in terms of exact works: for example, Lipatti played at least six Chopin Preludes, but exactly which ones he performed are unknown. Many of the works - particularly the four Beethoven Sonatas and the Schubert B-Flat Sonata! - are from his early performing years in the 1930s; he played the Waldstein throughout his career, however, and not only in the last few years of his life as his recording engineer Walter Legge erroneously reported. Some of the works that he did play in his later years include Bach Prelude and Fugues, Schumann's Études Symphoniques, Ravel's Le tombeau de Couperin, and Chopin's Fourth Ballade.

It is an enticing list that makes the lack of more recordings by this unique artist all the more regrettable. Let us hope that some other concert broadcasts or private recordings will be found!

Works for Solo Piano and Two Pianos

Albéniz

Iberia, Book 1 - 1. Evocación

Iberia, Book 1 - 2. El Puerto

Iberia, Book 2 - 3. Triana

Navarra (transcribed by Lipatti)

Petite serenade

Andricu

Two Dances

Two Pieces Op.18

Bach

Chorale in G Major, BWV 147 "Jesu, Joy of Man's Desiring" (arr. Hess)

Chorale Prelude, "Ich ruf zu Dir, Herr Jesu Christ" BWV 639 (arr. Busoni)

Chorale Prelude, "Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland" BWV 659 (arr. Busoni)

English Suite No.3 in G Minor, BWV 808

Italian Concerto, BWV 971

Partita No.1 in B-Flat Major, BWV 825

Pastorale in F Major for organ, BWV 590 (transcribed Lipatti)

Phantasy in A Minor, BWV 904

Preludes and Fugues from the Well-Tempered Clavier (at least 4)

Prelude and Fugue in E Minor for organ, BWV 533

Siciliano from Flute Sonata, BWV 1031 (arr. Kempff)

Toccata in D Major, BWV 912

Toccata in C Major, BWV 564 (arr. Busoni)

Bartók

Allegro barbaro

Six Dances in Bulgarian Rhythm (Mikrokosmos Vol.6)

Sonata for Piano

Beethoven

Piano Sonata No.7 in D Major, Op.10 No.3

Piano Sonata No.17 in D Minor, Op.31 No.2

Piano Sonata No.21 in C Major, Op.53 "Waldstein"

Piano Sonata No.23 in F Minor, Op.57 "Appassionata"

Berkeley

Concert Polka for Two Pianos

Brahms

Capriccio in D minor, Op.116 No.7

Intermezzo in A Minor, Op.116 No.2

Intermezzo in E-Flat Major, Op.117 No.1

Intermezzo in B-Flat Minor, Op.117 No.2

Intermezzo in E-Flat Minor, Op.118 No.6

Intermezzo in C Major, Op.119 No.3

Variations on a Theme by Haydn for Two Pianos

Waltzes Op.39 for Two Pianos (Nos. 1, 2, 5, 6, 10, 14, 15 - and perhaps others)

Brero

Five Preludes

Bull

Variations for Keyboard

Byrd

Various Pieces for Keyboard

Casella

Sonatina

Chopin

Ballade No.4 in F Minor, Op.52

Barcarolle in F-Sharp Major, Op.60

Étude in A Minor, Op.10 No.2

Étude in G-Flat Major, Op.10 No.5

Étude in C Major, Op.10 No.7

Étude in F Major, Op.10 No.8

Étude in E Minor, Op.25 No.5

Étude in A Minor, Op.25 No.11

Mazurka in E Minor, Op.41 No.1

Mazurka in B Major, Op.41 No.2

Mazurka in C-Sharp Minor, Op.41 No.4

Mazurka in C-Sharp Minor, Op.50 No.3

Nocturne No.8 in D-Flat Major, Op.27 No.2

Polonaise in E-Flat Major, Op.22

Polonaise in F-Sharp Minor, Op.44

Polonaise-Fantaisie in A-Flat Major, Op.61

various Preludes Op.28 (at least 6)

Rondo in F Major, Op.5

Scherzo No.1 in B Minor, Op.20

Scherzo No.3 in C-Sharp Minor, Op.39

Scherzo No.4 in E Major, Op.54

Sonata No.3 in B Minor, Op.58

Waltzes Nos.1 through 14

Waltz Op. Posth (which one is unknown)

Debussy

Arabesque (No.1 or 2)

Estampes No.2, "La soiree dans Grenade"

Étude pour les arpèges composés (and possibly others)

L'isle joyeuse

Images Book 1 No.1: "Reflets dans l'eau"

Images Book 1 No.2: "Hommage a Rameau"

Preludes (various)

Dohnányi

Capriccio in F Minor, Op.28 No.6

Enescu

Piano Sonata No.1 in F-Sharp Minor, Op.24 No.1

Piano Sonata No.3 in D Major, Op.24 No.3

Suite No.2 in D Major, Op.10

Variations on an Original Theme for two pianos, Op.5

De Falla

Ritual Fire Dance

Fauré

Impromptu No.3 in A-Flat Major, Op.34

Nocturne No.1 in E-Flat Minor, Op.33

Françaix

Concertino for two pianos

Handel

Suite No.3 in D Minor, HWV 428

Jora

Jewish March Op.8

Klepper

Two Dances

Lazar

Two Bagatelles

Lipatti

Compositions of childhood

Romanian Dances for two pianos

Three Dances for two pianos

Nocturne

Phantasie for piano solo

Sonatina for left hand

Suite for two pianos

Liszt

Concert Etude, "La Leggierezza", S.144

Concert Etude, "Gnomenreigen", S.145

Harmonies du soir

Mephisto Waltz No.1

Sonetto del Petrarca No.104

Mihalovici

Deux pieces impromptues, Op.19

Mozart

Piano Sonata No. 8 in A Minor, K.310

Sonata for Two Pianos in D Major, K.448

Mozart-Busoni

Duettino concertante for two pianos

Negrea

Sonatine Op.8

Nottara

Two Dances

Poulenc

Six Nocturnes

Ravel

Miroirs No.4, "Alborada del gracioso"

Miroirs No.5, "La vallee des cloches"

Le tombeau de Couperin

La Valse for two pianos

Scarlatti

Piano Sonata in E Major, L.23

Piano Sonata in G Major, L.387

Piano Sonata in D Minor, L.413

Piano Sonata in B-Flat Major

Piano Sonata in F Major

Piano Sonata in G Minor

Schubert

Impromptu No.2 in E-Flat Major, D.899 No.2

Impromptu No.3 in G-Flat Major, D.899 No.3

Piano Sonata No.21 in B-Flat Major, D.960

Allegro in A Minor for two pianos, D.947

Schumann

Blumenstück, Op.19

Carnaval, Op.9

Études Symphoniques, Op.13

Novelette No.2 in D Major, Op.21

Stravinsky

Danse russe (from "Petrouchka")

Sonata for piano

Weber-Corder

Invitation to the Dance for two pianos

Lipatti biographer Grigore Bargauanu and the collector Marc Gertsch, with a few additions made now - lacks some detail in terms of exact works: for example, Lipatti played at least six Chopin Preludes, but exactly which ones he performed are unknown. Many of the works - particularly the four Beethoven Sonatas and the Schubert B-Flat Sonata! - are from his early performing years in the 1930s; he played the Waldstein throughout his career, however, and not only in the last few years of his life as his recording engineer Walter Legge erroneously reported. Some of the works that he did play in his later years include Bach Prelude and Fugues, Schumann's Études Symphoniques, Ravel's Le tombeau de Couperin, and Chopin's Fourth Ballade.

It is an enticing list that makes the lack of more recordings by this unique artist all the more regrettable. Let us hope that some other concert broadcasts or private recordings will be found!

Works for Solo Piano and Two Pianos

Albéniz

Iberia, Book 1 - 1. Evocación

Iberia, Book 1 - 2. El Puerto

Iberia, Book 2 - 3. Triana

Navarra (transcribed by Lipatti)

Petite serenade

Andricu

Two Dances

Two Pieces Op.18

Bach

Chorale in G Major, BWV 147 "Jesu, Joy of Man's Desiring" (arr. Hess)

Chorale Prelude, "Ich ruf zu Dir, Herr Jesu Christ" BWV 639 (arr. Busoni)

Chorale Prelude, "Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland" BWV 659 (arr. Busoni)

English Suite No.3 in G Minor, BWV 808

Italian Concerto, BWV 971

Partita No.1 in B-Flat Major, BWV 825

Pastorale in F Major for organ, BWV 590 (transcribed Lipatti)

Phantasy in A Minor, BWV 904

Preludes and Fugues from the Well-Tempered Clavier (at least 4)

Prelude and Fugue in E Minor for organ, BWV 533

Siciliano from Flute Sonata, BWV 1031 (arr. Kempff)

Toccata in D Major, BWV 912

Toccata in C Major, BWV 564 (arr. Busoni)

Bartók

Allegro barbaro

Six Dances in Bulgarian Rhythm (Mikrokosmos Vol.6)

Sonata for Piano

Beethoven

Piano Sonata No.7 in D Major, Op.10 No.3

Piano Sonata No.17 in D Minor, Op.31 No.2

Piano Sonata No.21 in C Major, Op.53 "Waldstein"

Piano Sonata No.23 in F Minor, Op.57 "Appassionata"

Berkeley

Concert Polka for Two Pianos

Brahms

Capriccio in D minor, Op.116 No.7

Intermezzo in A Minor, Op.116 No.2

Intermezzo in E-Flat Major, Op.117 No.1

Intermezzo in B-Flat Minor, Op.117 No.2

Intermezzo in E-Flat Minor, Op.118 No.6

Intermezzo in C Major, Op.119 No.3

Variations on a Theme by Haydn for Two Pianos

Waltzes Op.39 for Two Pianos (Nos. 1, 2, 5, 6, 10, 14, 15 - and perhaps others)

Brero

Five Preludes

Bull

Variations for Keyboard

Byrd

Various Pieces for Keyboard

Casella

Sonatina

Chopin

Ballade No.4 in F Minor, Op.52

Barcarolle in F-Sharp Major, Op.60

Étude in A Minor, Op.10 No.2

Étude in G-Flat Major, Op.10 No.5

Étude in C Major, Op.10 No.7

Étude in F Major, Op.10 No.8

Étude in E Minor, Op.25 No.5

Étude in A Minor, Op.25 No.11

Mazurka in E Minor, Op.41 No.1

Mazurka in B Major, Op.41 No.2

Mazurka in C-Sharp Minor, Op.41 No.4

Mazurka in C-Sharp Minor, Op.50 No.3

Nocturne No.8 in D-Flat Major, Op.27 No.2

Polonaise in E-Flat Major, Op.22

Polonaise in F-Sharp Minor, Op.44

Polonaise-Fantaisie in A-Flat Major, Op.61

various Preludes Op.28 (at least 6)

Rondo in F Major, Op.5

Scherzo No.1 in B Minor, Op.20

Scherzo No.3 in C-Sharp Minor, Op.39

Scherzo No.4 in E Major, Op.54

Sonata No.3 in B Minor, Op.58

Waltzes Nos.1 through 14

Waltz Op. Posth (which one is unknown)

Debussy

Arabesque (No.1 or 2)

Estampes No.2, "La soiree dans Grenade"

Étude pour les arpèges composés (and possibly others)

L'isle joyeuse

Images Book 1 No.1: "Reflets dans l'eau"

Images Book 1 No.2: "Hommage a Rameau"

Preludes (various)

Dohnányi

Capriccio in F Minor, Op.28 No.6

Enescu

Piano Sonata No.1 in F-Sharp Minor, Op.24 No.1

Piano Sonata No.3 in D Major, Op.24 No.3

Suite No.2 in D Major, Op.10

Variations on an Original Theme for two pianos, Op.5

De Falla

Ritual Fire Dance

Fauré

Impromptu No.3 in A-Flat Major, Op.34

Nocturne No.1 in E-Flat Minor, Op.33

Françaix

Concertino for two pianos

Handel

Suite No.3 in D Minor, HWV 428

Jora

Jewish March Op.8

Klepper

Two Dances

Lazar

Two Bagatelles

Lipatti

Compositions of childhood

Romanian Dances for two pianos

Three Dances for two pianos

Nocturne

Phantasie for piano solo

Sonatina for left hand

Suite for two pianos

Liszt

Concert Etude, "La Leggierezza", S.144

Concert Etude, "Gnomenreigen", S.145

Harmonies du soir

Mephisto Waltz No.1

Sonetto del Petrarca No.104

Mihalovici

Deux pieces impromptues, Op.19

Mozart

Piano Sonata No. 8 in A Minor, K.310

Sonata for Two Pianos in D Major, K.448

Mozart-Busoni

Duettino concertante for two pianos

Negrea

Sonatine Op.8

Nottara

Two Dances

Poulenc

Six Nocturnes

Ravel

Miroirs No.4, "Alborada del gracioso"

Miroirs No.5, "La vallee des cloches"

Le tombeau de Couperin

La Valse for two pianos

Scarlatti

Piano Sonata in E Major, L.23

Piano Sonata in G Major, L.387

Piano Sonata in D Minor, L.413

Piano Sonata in B-Flat Major

Piano Sonata in F Major

Piano Sonata in G Minor

Schubert

Impromptu No.2 in E-Flat Major, D.899 No.2

Impromptu No.3 in G-Flat Major, D.899 No.3

Piano Sonata No.21 in B-Flat Major, D.960

Allegro in A Minor for two pianos, D.947

Schumann

Blumenstück, Op.19

Carnaval, Op.9

Études Symphoniques, Op.13

Novelette No.2 in D Major, Op.21

Stravinsky

Danse russe (from "Petrouchka")

Sonata for piano

Weber-Corder

Invitation to the Dance for two pianosDinu Lipatti’s Repertoire – Chamber Music

January 27, 2013 by

It is a little known fact that Dinu Lipatti was a skilled and enthusiastic chamber music performer. In his teens at the Ecole Normale de Musique in Paris, he had a trio with his fellow students Ginette Neveu and Antonio Janigro. He would tour Switzerland in 1947 with Janigro but it doesn't seem as though he played with Neveu again, a real loss for posterity, especially since both of them were EMI recording artists. While he recorded his godfather Georges Enescu's second and third Violin Sonatas with the composer performing, he didn't officially record any chamber music from the mainstream repertoire. However, he did record six works with Antonio Janigro as a test for Walter Legge in May 1947, but these were never released in his lifetime and only a few shorter works were found and issued in 1994 (this will be the subject of another post).

Below are all of the chamber music works that Dinu Lipatti is known to have played in public, and his private repertoire was doubtless larger: violinist Lola Bobescu spoke of them having played a Mendelssohn Trio together.

Bach

Sonata No.3 in E Major for Violin and Piano, BWV 1016

Sonata No.2 in D Major for Cello and Piano, BWV 1025

Beethoven

Sonata No.6 in A Major for Violin and Piano, Op.30 No.1

Sonata No.7 in C Minor for Violin and Piano, Op.30 No.2

Sonata No.10 in G Major for Violin and Piano, Op.96

Sonata No.3 in A Major for Cello and piano, Op.69

Trio No.4 in B Major, Op.8

Brahms

Liebeslieder Walzer Op.52 for Two Pianos and Singers

Sonata No.1 in E Minor for Cello and Piano, Op.38

Trio No.1 in B Major, Op.8

Chopin

Nocturne in C Sharp Minor for Cello and Piano, Op. Posth.

Enescu

Sonata No.2 in F Minor for Violin and Piano, Op.6

Sonata No.3 in A Minor for Violin and Piano, Op.25

Impressions d'enfance (Suite for Violin and Piano), Op.28

Fauré

Sonata No.1 in A Major for Violin and Piano, Op.13

Sonata No.2 in E Minor for Violin and Piano, Op.108

'Après un rêve' for Cello and Piano (after Melodie Op.7 No.1)

Franck

Sonata in A Major for Violin and Piano

Lipatti

Sonatina for Violin and Piano

Fantaisie cosmopolite for Violin, Cello, and Piano

Mozart

Sonata in G Major for Violin and Piano, K.379

Sonata in A Major for Violin and Piano, K.526?

Ravel

'Pièce en forme de Habanera' for Cello and Piano

Rimsky-Korsakov

'The Flight of the Bumblebee' for Cello and Piano

Schubert

Trio No.1 in B-Flat Major, D.898

It is a little known fact that Dinu Lipatti was a skilled and enthusiastic chamber music performer. In his teens at the Ecole Normale de Musique in Paris, he had a trio with his fellow students Ginette Neveu and Antonio Janigro. He would tour Switzerland in 1947 with Janigro but it doesn't seem as though he played with Neveu again, a real loss for posterity, especially since both of them were EMI recording artists. While he recorded his godfather Georges Enescu's second and third Violin Sonatas with the composer performing, he didn't officially record any chamber music from the mainstream repertoire. However, he did record six works with Antonio Janigro as a test for Walter Legge in May 1947, but these were never released in his lifetime and only a few shorter works were found and issued in 1994 (this will be the subject of another post).

Below are all of the chamber music works that Dinu Lipatti is known to have played in public, and his private repertoire was doubtless larger: violinist Lola Bobescu spoke of them having played a Mendelssohn Trio together.

Bach

Sonata No.3 in E Major for Violin and Piano, BWV 1016

Sonata No.2 in D Major for Cello and Piano, BWV 1025

Beethoven

Sonata No.6 in A Major for Violin and Piano, Op.30 No.1

Sonata No.7 in C Minor for Violin and Piano, Op.30 No.2

Sonata No.10 in G Major for Violin and Piano, Op.96

Sonata No.3 in A Major for Cello and piano, Op.69

Trio No.4 in B Major, Op.8

Brahms

Liebeslieder Walzer Op.52 for Two Pianos and Singers

Sonata No.1 in E Minor for Cello and Piano, Op.38

Trio No.1 in B Major, Op.8

Chopin

Nocturne in C Sharp Minor for Cello and Piano, Op. Posth.

Enescu

Sonata No.2 in F Minor for Violin and Piano, Op.6

Sonata No.3 in A Minor for Violin and Piano, Op.25

Impressions d'enfance (Suite for Violin and Piano), Op.28

Fauré

Sonata No.1 in A Major for Violin and Piano, Op.13

Sonata No.2 in E Minor for Violin and Piano, Op.108

'Après un rêve' for Cello and Piano (after Melodie Op.7 No.1)

Franck

Sonata in A Major for Violin and Piano

Lipatti

Sonatina for Violin and Piano

Fantaisie cosmopolite for Violin, Cello, and Piano

Mozart

Sonata in G Major for Violin and Piano, K.379

Sonata in A Major for Violin and Piano, K.526?

Ravel

'Pièce en forme de Habanera' for Cello and Piano

Rimsky-Korsakov

'The Flight of the Bumblebee' for Cello and Piano

Schubert

Trio No.1 in B-Flat Major, D.898